Messages are all good and well, indeed a vital part of communications. But a common fault amongst those trying to communicate messages is the belief that if they put the message out often enough and loud enough it’ll get through – just keep on hammering it home and the audience will get the message.

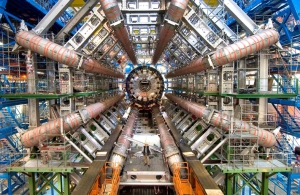

But messages do not get transmitted through a vacuum. They exist amongst many other messages, borne of plain information or of more complex relationships, in contemporary space, and put simply they create narratives – stories. And those stories can be deep, complex, long-lived and ingrained. They have a temporal quality, based upon a remembered past. Simple messages, even if repeated and loud, may bounce off. More successful messages may shift the narrative, but given the temporal and complex nature of these narratives, with a multitude of variables, may shift it in unexpected ways. An analogy could be taken from sub-atomic physics, where many particles (messages) may miss the target atom (narrative), a single high velocitycollision of one particle (message) into an atom (narrative), neither adds to the atom (narrative) nor displaces another particle (message) but often creates something quite different (a new narrative). The atomic scientist applies his or her brainpower to understand what this new something will be and how it can be controlled. The art of strategic narrative imitates that.

CERN and sub-atomic physics - this is real science ...

However, where the scientific example is highly rules based and can acceptably aim for a degree of control, art is more abstract and irrational. Which brings up the main element of narrative theory. Narrative theory presupposes that people are essentially storytellers, make decisions based upon their own condition, that condition is borne of culture, history and character, the world consists of sets of stories which we choose to frame our lives. This is slightly out of kilter with a more scientific and rational approach, whereby people are rational, persuaded by argument and the world is a logical place.

... and this is art (about storytelling)

From narrative theory, concentrating on the rational, well-meant messages and not the narrative can often result in unintended results. Using master messages as one’s starting point is asking for trouble. And even if one takes account of the narrative it is often one’s own narrative, not the narrative existing in temporal and complex space – one’s own story often bears no resemblance to the story ‘out there’. And understanding culture, poilitics, media environments and history will be to little avail if one does not understand how they contribute to existing narratives and what those narratives are.

The advent of new, social, digital media complicates all this. Whilst many claim that it dilutes the temporal aspect, the memory, by diffusing its constituents, others talk of it hardening history through the ability to capture, archive, retrieve and distribute digital information, creating definitive spikes in historical discourse (much like the long tail phenomena, whereby expontential traction is afforded to the few). Alongside this aspect of memory comes the idea of memes, gathering pace amongst practitioners and acdemics alike.

But at heart, the art of the strategic narrative involves the understanding of how narratives exist, what creates such narratives, accepting that they are fundamental to the communicative environment and have a temporal quality, and realising that domination of an existing narrative is not practical (although the generation of a dominant narrative is). To the communications practitioner it involves the understanding of one’s own narrative in the minds of others, accepting that it may be different from the intended, grasping how and why that is so, and developing messages that will influence that narrative, not ones that will just bombard it ineffectually.

Taking a look at many public diplomacy, strategic communications and PR campaigns, an obvious hankering for an ordered universe, where stories can be controlled, seems to be the norm. A more enlightened, deeper understanding of narratives and their place in publics’ psyches may pave the way to developing the elusive art of the strategic narrative.

cb3blog

Glad you like the site design – it’s fairly basic – using a straightforward wordpress theme (contempt) and little bits of basic HTML in the text widgets. Check out wordpress forums for more info on making maximum use of widgets etc. Good luck.